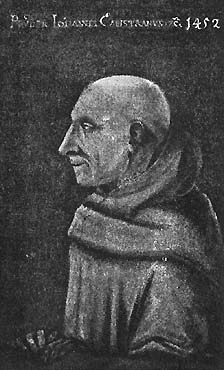

Jan Kapistrán

| (1386 - 1456) | Franciscan priest |

From the mid 1200\'s, the

order of brothers established by Saint Francis from Assisi in 1209

had been split into two branches of moderate members (conventuals

and Minorites) and more rigid members (observants and Franciscans).

In the 15th century Jan Kapistrán was one of the leaders of the

then more independent Franciscan branch and became a famous priest.

For his preaching ability the Pope sent him together with the

cardinal Mikuláš Kusánský on a great mission to Germany in 1451 to

suppress the spreading Hussite order. Arising Franciscans needed

the saints to overtake the Conventuals, and Kapistrán thought that

by converting Bohemia to Catholicism he could become one of them.

During the mission emperor Friedrich III. became well-disposed

towards Kapistrán and recommended him to the protection of Ulrich II. von

Rosenberg. Ulrich was one of the few Bohemian statesmen of a

truly international level who had contacts with the emperor and

prominent German and Austrian families. His leading position among

the Catholic aristocracy in Bohemia excited a feeling abroad that

he was absolutely devoted to Catholicism and wanted the Hussites

defeated - it was for this reason that Kapistrán placed his hopes

in Oldřich. When he did not receive an invitation from Jiří of

Poděbrady after his successful stay in Moravia, he came to Český

Krumlov on 15 October 1451 on Ulrich´s request. He helped to

stabilize relations in a local Minorite

monastery as well as influencing Ulrich von Rosenberg who had

abandoned his estates and handed over the rule of his Rožmberk

house to his son Heinrich. Kapistrán´s main objective in Bohemia

was Prague where he wished to hold dispute with the elected

archbishop of Prague Jan Rokycan. But an indignation was rising in

Prague against Kapistrán because he was constantly attacking the

compacts and acceptance of the Utraquists. Even the Catholics,

including Ulrich von Rosenberg, did not want to return to the

pre-Hussite situation which would have revived the power of the

Catholic church. The priest\'s choleric temper was apparent even in

the way that he spoke about Krumlov, the town of his protector, in

a response to Rokycan. Jan Kapistrán was evidently dissatisfied

with the conditions of the dispute because the location seemed to

be too vulgar for him. According to him there were, excepting the

family of Jindřich from Lipé, only solders and herdsmen in all of

Český Krumlov in front of whom Rokycan wanted to show his

adroitness. Maybe he was afraid of speaking in front of

well-educated men. Even Mikuláš Kusánský himself had to curb his

persistent attacks against Rokycan. Kapistrán stayed in Český

Krumlov a month and during this time he was miraculously healing

the sick, as usual, and winning people over to his religious

order.

From the mid 1200\'s, the

order of brothers established by Saint Francis from Assisi in 1209

had been split into two branches of moderate members (conventuals

and Minorites) and more rigid members (observants and Franciscans).

In the 15th century Jan Kapistrán was one of the leaders of the

then more independent Franciscan branch and became a famous priest.

For his preaching ability the Pope sent him together with the

cardinal Mikuláš Kusánský on a great mission to Germany in 1451 to

suppress the spreading Hussite order. Arising Franciscans needed

the saints to overtake the Conventuals, and Kapistrán thought that

by converting Bohemia to Catholicism he could become one of them.

During the mission emperor Friedrich III. became well-disposed

towards Kapistrán and recommended him to the protection of Ulrich II. von

Rosenberg. Ulrich was one of the few Bohemian statesmen of a

truly international level who had contacts with the emperor and

prominent German and Austrian families. His leading position among

the Catholic aristocracy in Bohemia excited a feeling abroad that

he was absolutely devoted to Catholicism and wanted the Hussites

defeated - it was for this reason that Kapistrán placed his hopes

in Oldřich. When he did not receive an invitation from Jiří of

Poděbrady after his successful stay in Moravia, he came to Český

Krumlov on 15 October 1451 on Ulrich´s request. He helped to

stabilize relations in a local Minorite

monastery as well as influencing Ulrich von Rosenberg who had

abandoned his estates and handed over the rule of his Rožmberk

house to his son Heinrich. Kapistrán´s main objective in Bohemia

was Prague where he wished to hold dispute with the elected

archbishop of Prague Jan Rokycan. But an indignation was rising in

Prague against Kapistrán because he was constantly attacking the

compacts and acceptance of the Utraquists. Even the Catholics,

including Ulrich von Rosenberg, did not want to return to the

pre-Hussite situation which would have revived the power of the

Catholic church. The priest\'s choleric temper was apparent even in

the way that he spoke about Krumlov, the town of his protector, in

a response to Rokycan. Jan Kapistrán was evidently dissatisfied

with the conditions of the dispute because the location seemed to

be too vulgar for him. According to him there were, excepting the

family of Jindřich from Lipé, only solders and herdsmen in all of

Český Krumlov in front of whom Rokycan wanted to show his

adroitness. Maybe he was afraid of speaking in front of

well-educated men. Even Mikuláš Kusánský himself had to curb his

persistent attacks against Rokycan. Kapistrán stayed in Český

Krumlov a month and during this time he was miraculously healing

the sick, as usual, and winning people over to his religious

order.

Kapistrán still could not get to Prague and, with his idea to humiliate the heretical Bohemia, he turned the aristocracy of both religions against himself even more. With hope he left in the middle of year to Řezno where negotiations about a meeting of Mikuláš Kusánský with the Czechs should have taken place, although they never did. After Oldřich from Rožmberk and his son Jindřich disappointed him by submitting to Jiří of Poděbrady, Kapistrán tried in vain to influence the Czech king Ladislav Pohrobek. Considering his mission to Bohemia unsuccessful, Kapistrán allowed himself to be won over by Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini to fight against the Turks, who had taken over Constantinople in 1453. Kapistrán died shortly after he helped Jan Hunyady successfully defend Belgrade against the Turks in 1456. The miracles Kapistrán had been performing during all his missions allegedly continued after his death, and it was for their sake that in 1690 he was declared a saint.

(jh)