Historical Routes in the Český Krumlov Region

From long ago paths led across the countryside of the Czech, which enabled long distance business contacts between Bohemia and the Alpine countries. Their destination was mainly Praha, as the natural centre of the Czech country, and an gateway for other travels to the German countries, Poland, Russia, and towards the Baltic sea. The crossing over the thick and extensive expansion of border forests which were sparsely populated, was during the Middle Ages only by narrow footpaths, which where difficult to traverse. Their direction went across passable sections of the mountainous region of Šumava, and along the flow of the Vltava river, which divided the region into two different sections. At the beginning the paths had a width sufficient only for two donkeys with goods, but later on the paths were properly strengthened and widened.

The country paths had a great influence on the colonisation of the border regions. From the 13th century royal towns, and serfs villages were set up alongside these paths which brought through their gates income from tolls, and reaped the rewards from successful business connections. The road maintenance and management was one of the "land responsibilities" of the nobility and serfs, who obtained the finances for the repair and maintenance of these paths through collecting tolls. Money also came into the royal coffers from collecting customs duty and excise on imported goods. The customs officers collected the taxes on the so-called "public" therefore, permissible paths, which were not allowed to be avoided. If somebody missed this customs point and was caught, his transport and his goods were confiscated. One half of the property went to the king's purse, and the other to the town which the person tried to cheat and take away the opportunity of its income. Even though the penalties were high, the traffic across the "side" roads, by the authority forbidden ones, grew. Due to the traffic on these paths, the thick border forests became sparse, which endangered the safety of the country.

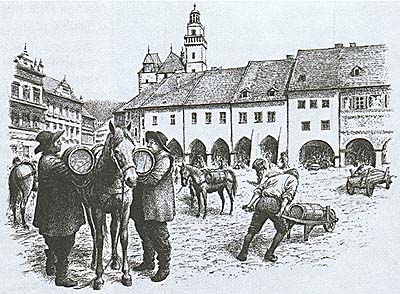

The goods carried on the roads into Bohemia were mainly salt, linen, good quality cloth, silk, arms, wine, sea water fish, tropical fruit, foreign spices and other grocery products. We exported wheat, butter, cheese, cattle, fresh water fish, malt, beer, wax, honey, and other farm and crafted products.

The oldest and the most frequented road was the Zlatá Stezka (Golden Path). This path led from the Bavarian town of Passau across Freyung, Bischofsreuth, České Žleby, the Hus castle and Libínské Sedlo and on to Prachatice. From here it carried on to Netolice, Vodňany, Protivín and Písek to Praha. Most likely the path was already being used from the 11th century. In the 14th century a road branched off the existing path, leading from Passau across Freyung, Kvilda, Horská Kvilda to Kašperské Hory. Another branch went across Bavarian Grafenau to Březník, Horská Kvilda and Modrava on to Sušice, Klatovy and Plzeň. Customs points were set up across the borders, from these gradually towns and villages developed. This was the way the town of Prachatice was established, this town quickly became wealthy, mainly thanks to its exclusive right of selling and storing Bavarian salt. With the view of the profitability of buying and selling salt, this path was renamed "Zlatá" (Golden). In the 16th century salt was transported on this path to the country by 1,200 - 1,300 donkeys a week. After 1706, when the emperor's salt, which was imported from Gmünden, pushed out the salt from Bavaria, and the store was transferred from Prachatice to Český Krumlov, and the Zlatá (Golden) path more or less lost its trading importance.

The Linz path had been used from the Middle Ages as a connection between Bohemia and the Austrian countries, and was mainly used for the transportation of salt and cattle. The first written notification of this path exists from 906. The path led from Linz across Leonfelden and Studánky to Vyšší Brod, and by Rožmberk it crossed the stream to the right side of the Vltava river, and continued across Český Krumlov, Boletice, Chvalšiny, Smědeč, and Lhenice to the Zlatá stezka towards Netolice and on to Protivín, Písek and to Praha. From the town of Leonfeld the road branched off towards Frymburk later, where a wooden bridge stood across the Vltava river. Further on this branch of the Linz path was called Kaplická path, which led from Linz to Cáhlov (Freistadt) and from here across Dolní Dvořiště, Kaplice, Velešín and Doudleby to České Budějovice and on to Soběslav, Tábor and then to Praha. The Linz path was very important for long

distance transport of

goods, and also for local connections between the town of Český

Krumlov, Rožmberk and Vyšší Brod. It was used by the nobility as

well as the connection for the local tradesmen from villages and

towns. Information from the 15th century states that the path was

used for transporting salt, Venetian goods and iron from

Styria.

distance transport of

goods, and also for local connections between the town of Český

Krumlov, Rožmberk and Vyšší Brod. It was used by the nobility as

well as the connection for the local tradesmen from villages and

towns. Information from the 15th century states that the path was

used for transporting salt, Venetian goods and iron from

Styria.

The Gmünden path sometimes called the Austrian (Rakouská) led from the Austrian castle of Raabs, from Moravia to Bohemia across Slavonice through the county gate between Landštejn and Pomezí. This path went on to Staré Město pod Landštejnem, Nová Bystřice and Stráž nad Nežárkou to the Linz path. Later on it turned towards the town of Jindřichův Hradec.

The Vitorazská (Česká) path originated most likely in primeval times. It started by the Austrian monastery of Světlá (Zwettl) and led across Vitoraz (Weitra) to the county gates near the later town of Nové Hrady, and across Žár, Trhové Sviny, and Doudleby towards České Budějovice, where it joined the Linz path. Further on the road branched off from Nové Hrady across Stropnice, Malonty, Lichtenau to Cáhlov (Freistadt).

The countryside of South Bohemia was interwoven with a network of other paths. The Březnická path existed from the 11th century and connected the town of Zwiesel in Bavaria, Březnice and Hartmanice. Another path from the end of the 13th century most likely went from Haslach in Austria to Svatý Tomáš, Frymburk and Český Krumlov. It is also possible that in the 13th century the path from the town of Schlägl in Austria across Kyselov and Dolní Vltavice to Hořice na Šumavě and to Český Krumlov was also used.

Hornoplánská path was named for the trade traffic with salt , it went from the Bavarian town of Waldkirchen across Plechý to Horní Planá. From the end of the 14th century the salt was also transported on the Vimperská path, which led from Röhrbach in Bavaria across Lipka and Horní Vltavice to Vimperk.

The roads were very often in a catastrophic state, and the provincial council had to instigate the repair of the roads, which were in a "bad way, overgrown, slushy, full of holes and potholes, and muddy", they were endangering the life of travellers and their horses. The roads were narrow and muddy, and during prolonged rain in certain places they remained un- passable. Their foundation was not solid apart from in swampy areas the road was strengthened with planks of wood, which had to be regularly replaced, to maintain the passable road. The bridges used to be wooden, sometimes with a roof over the top. Quite often they were missing altogether begin swept away by the spring waters. The maintenance of the roads and bridges, right up to the 18th century, was the responsibility of the nobility whose land they went across. Expenses which arose from the maintenance and repairs of the roads and bridges were supposed to be met from the taxes collected. The nobility collected the taxes, but their responsibility towards the maintenance of the roads was not adhered to stringently.

The travellers on their way were in danger of "highwaymen, scoundrels, evil-doers, destroyers of land, Petrov's band, assassins, tramps and reckless people". To make the road safer, the shrubbery and trees alongside the road was supposed to be cut back as per legislation from 1578 to the width of 32 meters.

Up to the 19th century it was possible to see stage coaches and farm wagons and carrier wagons covered with canvas or coaches of different kinds, which were pulled by horses. They were used as public transport, but also for the transport of groceries and other goods including mail. Right up to the end of 16th century mail was delivered by carriers, special officers or the nobility's messengers, who went on the road in the service of individual noble family, Estates, towns and monasteries. Apart from the ways we mentioned the news were carried across by travellers, Jews, priests, monks and travelling students - vagrants, butchers, grocers, travellers resembling businessmen, and other "people travelling across the world". In 1748 mail transport was nationalised in the Bohemian and Austrian countries, which laid the foundation for its further development. The collection of post and its distribution was the responsibility of the emperors postmasters in special post office stations. Gradually the network of post-office stations grew and in more remote areas of the region separate collection places were established. The main routes in South Bohemia which were important, belonged the connection between Vienna and Praha, were covered twice a week and from the middle of the 18th century an effort was made to set up a daily postal service (Journaliere) between Vienna and Praha.

From the second half of the 18th century an effort was made to restructure and rebuild a proper network of main roads, to which the Linz path belonged. It led from Praha across České Budějovice, and Dolní Dvořiště to Linz. From 1804 the building of the road began following a new system which was called "voluntary competition" between the nobility and the serfs, who took over the responsibility from the previous agreement with the village magistrate, to make a compulsory contribution to the building of the road as per their tax liabilities, and the distance from the village to the named road. The serfs had to take over the manual responsibility of labour and transportation of materials. The nobility purchased this material and at their own expense carried out the building of canals, bridges and other small work. The man made roads were 30 - 42 feet wide, with a firm base and ditches on both sides. The old wooden bridges were also not suitable for the increasing traffic, and were replaced with metal bridges. The building of the main road network was completed in the middle of the 19th century. When the building was finished the edges of the roads were to be firmed up by planting trees . Alongside the main roads, but also the side roads had avenues of some locust-trees, and poplars, but it was mainly fruit trees that were planted. For example from the documentation we have from 1832, the roads in Bohemia were lined with 544,014 trees, which noticeably changed and altered the appearance of the countryside. Hostels and pubs were re-opened or new ones were set up alongside the newly built roads, which were a welcoming sight for the carriers and travellers. In the 19th century, the town walls and gates started to be demolished, and around the main roads new towns sections quickly grew up.

The change in the transport technology, and the vehicles used, led to new alterations to the surface of the roads during the first half of the 20th century. The developing automobile industry required a long term maintenance of the roads, and a permanent surface in the form of concrete and tarmac. The roads, even during the present time have maintained on the whole, the original direction of the Middle Ages paths.

(mh)

Further information:

Salt

Route

History

of Transportation in the Český Krumlov Region